Introduction

Migrant participation has been increasingly hailed as a prerequisite to meaningful policymaking and implementation in the field of integration. Notably, the new Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion, published by the European Commission (EC) to promote integration across the EU in the 2021-2027 period, specifically urges to step-up the participation of migrants in all stages of the integration process. With this scope, the Commission launched at the end of 2020 an Expert Group on the view of migrants to directly hear from third-country nationals (TCNs) in the conception and implementation of asylum, migration and integration policies.

With close to 34 million EU residents born outside the EU (Eurostat, Population data 2019) and large historic diasporas across the EU countries, ensuring migrant participation and representation should be an easy task. Yet, little is actually known about how migrants are able to associate across the different EU countries. What types of structures do they organise through in the different EU regions? Are migrants even able to form their own associations? What activities do they engage in on a national and local level, and are there any successes that can be traced back to them?

With this analysis, EWSI provides a glimpse into some of the most active – and, where possible, policy-relevant – migrant-led structures in the 27 EU countries (EU-27). The analysis is exploratory in nature, as the list of migrant-led structures is not exhaustive but focused on prominent examples identified by our network through desk research.

Key findings

- Multi-ethnic migrant-led structures catering to diverse interests are prevalent in the Northern and Western EU countries, or in traditional migration destinations.

- Organisations serving just one historically present ethnic or religious group are the most common type of association in the Central, Eastern and Baltic countries. In the same region, refugee-led and migrant-women-led organisations are least popular.

- Only a quarter of the most active migrant-led organisations across the EU countries are also represented on a EU or international level through membership in umbrella organisations.

- Advocacy is the most common line of work for migrant organisations but in the Central, Eastern and Baltic countries cultural and educational activities are prevalent instead.

- Organisations engage in various type of work, with the different groups of migrants however often focusing on the specific issues affecting them, with curbing sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) for example a priority for women-led groups, while second-generation migrants often advocating for easier access to citizenship.

- Overall, national bureaucratic realities define to what extent and in what form migrants may organise and engage in different issues. Affecting policy change is not an easy task, with some notable exceptions and ongoing initiatives to keep track of noted below.

Methodology

To see what structures EWSI classified as migrant-led and included in this analysis, see our notes on the methodology here. In general terms, the structures reviewed in the current study go beyond migrant associations and include other forms of organisations such as foundations and civil society organisations in order to accommodate the various legal realities faced by TCNs in the different EU countries.

Across the EU-27, 130 structures were identified on a national level, and another 31 on a regional or local level. The set does not claim to be representative of all migrant-led organisations. Rather, it provides an initial glimpse into a few most active structures, as identified by the EWSI Editorial Team through desk research.

The analysis compares migrant organisations from three EU regions which emerged from the initial data set given these countries’ commonalities in terms of migration history and prevalence, as well the overall ability of migrants to organise. The EU-27 are thus segmented into Northern and Western countries, Central, Eastern and Baltic countries, and Southern countries.

Types of migrant organisations

In sampling, EWSI attempted to include a variety of structures based on who leads them. It emerges that close to half the organisations working on a national level – or 43% – are migrant-led. The same type leads on a local level where it represents 32% of all structures.

Second-generation or youth-led organisations come next in popularity on a national and local level alike, representing 19% of each set. Women-led organisations are among the least common on a national level with 12%, although the same type is more popular in a localised context where it comes second together with youth groups with a 19-percent share. Second-to-last in both sets are the structures classified under ‘other migration-related diversity’. These organisations have diverse leaders who have come together based on another commonality – in other words, they may be a mix of refugees, migrant women and youth brought together rather because they are all Muslim, or workers. Finally, least represented on both levels are refugee-led structures.

Zooming in on the three EU regions on a national level, notable refugee-led structures are least present in the Central, Eastern and Baltic region, which also include the countries with the fewest international protection applications (Eurostat, Asylum statistics 2020). Similarly, migrant-women-led organisations appear less active there unlike in the Northern and Western countries where they come second together with structures classified as other migration-related diversity. Second-generation and youth-led organisations, on the other hand, are most prevalent in the Central, Eastern and Baltic countries. As the set of local organisations is smaller, such further breakdown per regions is not meaningful.

The Northern and Western European countries see the oldest organisations on a national level, although on a local, there are notable earlier examples in the Southern countries.

When looking at the organisations based on their leadership type, on both national and local levels, migrant-led structures are the oldest while refugee-led ones have been formed most recently.

Combing the national-level set based on both type and region, both migrant-led and migrant-women-led organisations were founded noticeably earlier in the Northern and Western countries than in the rest of the EU. Organisations falling under ‘other migration-related diversity’, on the other hand, were established later in the Central, Eastern and Baltic states.

Composition

In addition to their varied leadership, organisations also differ in terms of the composition of the migrant communities they serve.

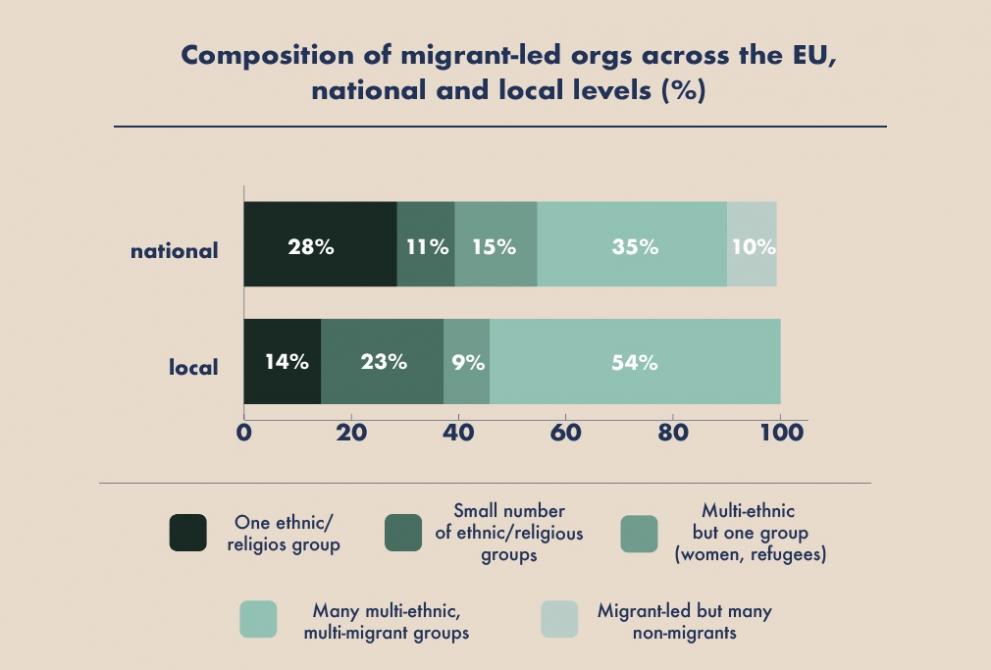

On a national level, 35% of all organisations cater to the interests of many multi-ethnic and multi-migrant groups, while 28% are dedicated to just one ethnic or religious group. ‘Ethnic’ here is understood as relating to a specific group with common national, religious, linguistic or cultural origins and is chosen over the more legalistic term ‘national’. The third most commonly found type with 15% serves multi-ethnic groups gathered together based on a specific characteristic, such as being women, or speaking a certain language. On the local level, however, over half of the organisations serve varied communities, despite their limited geographical scope: 54% are classified under many multi-ethnic and multi-migrant groups. Next are those defined under ‘small number of ethnic or religious groups’ (23%), usually bound together above all based on location. Organisations which are migrant-led but include and serve many non-migrant members take up a 10-percent share on a national level, but are not found in the local sample of most active structures.

Grouping the national-level organisations based on region, structures serving one ethnic or religious group are most pronounced in the Central, Eastern and Baltic countries with 42%, taking over the lead over many multi-ethnic and multi-migrant groups (37%). The same region sees no multi-ethnic groups serving just one category of migrants, however – for example, organisations led by women of different ethnic backgrounds have expanded the scope of their beneficiaries to non-women groups too, based on need.

Tallying the composition of communities served against the type of organisation, half of the arguably most-diverse structures – those which are migrant-led and which represent the interests of many multi-ethnic and multi-religious groups – are based in the Western and Northern EU countries.

Similarly, the region is a home to the majority of those women-led, second-generation, as well as other migration-related diversity structures, which are working for the advancement of mixed communities, rather than a single ethnic or religious group.

Most common activities and notable examples of migrant-led work

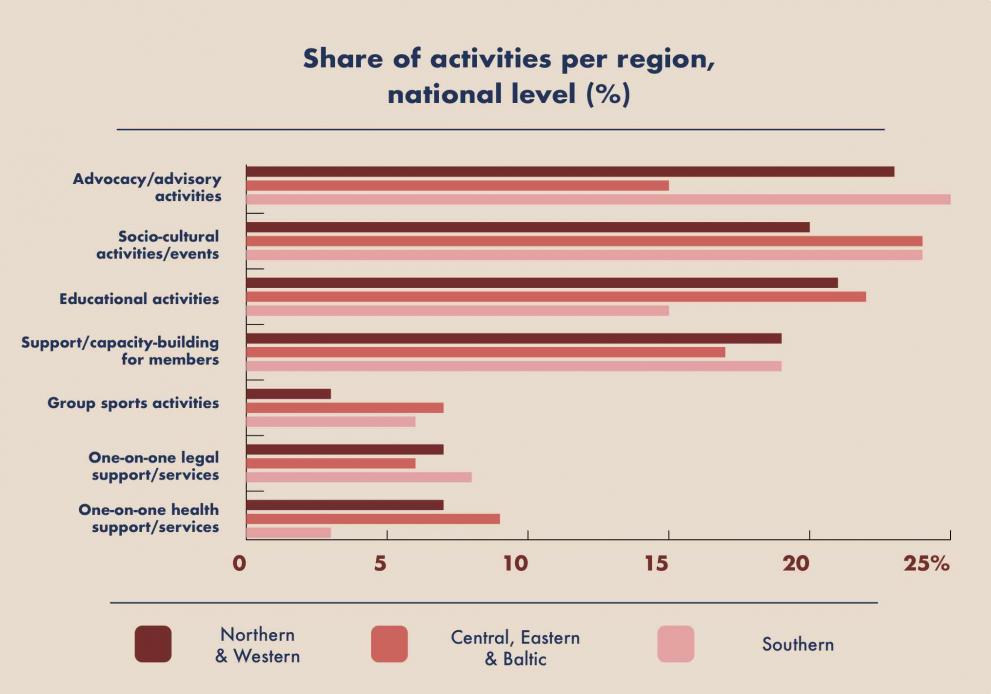

Most organisations have diverse portfolios. A comparison of the activities across regions and type of organisation reveals that on a national level, the majority of migrant-led structures are involved in socio-cultural activities (104 organisations) and advocacy and advisory activities (103), followed closely by work devoted to educational activities (94) and the provision of capacity-building and support for members (88). One-on-one legal support and individual health services are respectively provided by 34 and 32 migrant structures. Sports activities are the least represented, with only 22 organisations involved in such. A very similar dynamic is observed on a local level.

On a regionalised basis on the national level, advocacy work leads in all but the Central, Eastern and Baltic countries, where migrants appear to face more bureaucratic burdens to participation. Cultural activities are strongly presented across the EU-27, while educational support is a bit less prominent in the Southern countries.

Legal and health services, albeit rarer, are provided by a variety of organisation types. Overall, whenever sports activities are organised, they are mostly provided in a bundle with other services, often ad-hoc in the context of specific programmes or events such as annual festivals. There is just one organisation dedicated exclusively to sports – Kabubu in France – which provides TCNs with the opportunity to gain a professional qualification in sports and animation, with language and social support also embedded in the training.

As noted earlier, the majority of the most active structures belong to the migrant-led category. What are some notable successes of such migrant organisations? In Poland, Fundacja Rozwoju Oprócz Granic [Foundation for Development Beyond Borders] and Fundacja Nasz Wybór [Our Choice Foundation] were part of the Immigrants for Abolition Committee whose campaigning was key to the 2012 provisions allowing the largest possible number of foreign citizens to regularise their residence status (the so-called abolition); read more here.

In Sweden, in addition, Samarbetsorgan för etniska organisationer i Sverige (SIOS) [Forum for Cooperation between Ethnic Organisations in Sweden] is a migrant-led, politically and religiously independent association bringing together voluntary migrant groups since 1972. In addition to often consulting state bodies, SIOS has been running the independent anti-discrimination agency Antidiskrimineringsbyrån (ADB) Stockholm Syd which provides legal counselling to persons who have been discriminated on the basis of gender, ethnicity, religious or other beliefs, sexual orientation and age. Anti-discrimination agencies across Sweden have been successful in winning cases in court.

Organisations headed by second-generation migrants or youth leaders come second in popularity on both national and local level. Despite recommendations that birthright citizenship fosters integration – and would inevitably empower second-generation migrants in better maneuvering national bureaucracies – policies across the EU diverge. In Demark, for example, access to citizenship has been increasingly more obfuscated, while Portugal, on the other hand, has been lifting barriers to naturalisation. Mobilised around the birthright citizenship issue, some of the most active second-generation migrant organisations identified in Italy, Rete G2 – Seconde Generazioni [Second Generations Network] and Coordinamento Nazionale Nuove Generazioni Italiane (CONNGI) [National Coordination of the New Italian Generations] - have been campaigning as part of a larger migrant-led front for better access to citizenship over the last decade, with a hearing at the Constitutional Affairs Committee taking place in 2020. However, the reform of the Italian citizenship law has so far stalled.

Another interesting example is Federatia Tinerilor Romani de Pretutindeni (FTRP) [Federation of Young Romanians from Everywhere] whose members comprise of students of Romanian descend coming from third countries such as Moldova and Ukraine. The organisation has been providing support to these students since 2019, with some members successfully acquiring Romanian citizenship.

In terms of activities, educational support in general is a common line of work across second-generation organisations, which are also often engaged in mentoring schemes and lobbying for better access to rights. The same is true on a local level, where some second-generation structures have also been involved in cultural activities, as well as in providing shelter to young unaccompanied minors, as is the case of the organisation Minor-Ndako working in Brussels, Belgium.

Finally, this type of organisations has also been able to adapt to and gain prominence through their response to pertinent issues such as the COVID-19 pandemic. An example comes from the members of the Vietnamese community in the Czech Republic who, through their organisations, successfully run a social media campaign, #VietnamciPomahaji [The Vietnamese Help], and provided much-needed support in the mobilisation against the virus.

Women-led organisations are often devoted to combating sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). A notable example here is Akina Dada wa Africa (AkiDwa) [Sisterhood in Swahili], an organisation comprising of migrant women of diverse background, whose work led to the Irish Criminal Justice Act 2012 which criminalised female genital mutilation (FGM).

In addition, with the COVID-19 pandemic exposing women trapped in lockdown to an increased risk of domestic and SGB violence, the Migrant Women Association Malta (MWAM) has been able to quickly mobilise and provide assistance on the ground – find a good practice dedicated to their work here.

And just as migrant women often face multiple forms of discrimination, there are notable examples an intersectional approaches interwoven in their work. In Austria, in addition to producing research, the Autonomes Zentrum von und für Migrantinnen (MAIZ) [Autonomous Centre by and for Migrant Women] engages in activism and runs a dedicated space, also providing counselling to migrant sex workers.

The only notable migrant organisation identified in Bulgaria, finally, is again women-led – the Council of Refugee Women in Bulgaria (CRW). Its work however transcends beyond catering to the specific needs of women and instead has become a household name in the field when it comes to lobbying, mediation, as well as providing assistance to diverse migrant populations.

Refugee-led organisations, which are among the rarest on both national and local levels, also have a diverse scope of work and vary in terms of the populations they assist. An example is Convivial, a refugee-led organisation in Belgium, currently also involved in the provision of integration training programmes and language classes mandatory for most immigrants in Belgium. Since 2019, Convivial has expanded its work to support other types of immigrants, although it still runs its refugee-specific courses. On the other hand, in Finland, relevant associations often focus on the advancement of a specific ethnic group such as the Somali, Afghan or Kurdish refugee communities.

In term of successes, the work of the born-in-protests Movement of Asylum Seekers Ireland (MASI) helped create in 2015 the so-called McMahon report to improve the Direct Provision – the Irish asylum seekers accommodation system. The recommendations have largely not been implemented yet but small progress has been made. In addition, through extensive campaigning, MASI managed to lift the blanket ban on asylum seekers’ right to work in Ireland in 2018 – see the latest here.

Looking forward to the new 2021-2027 EU financial period, in addition, the Greek Forum for Refugees, together with other migrant-led structures, shared recommendations for the better, less-fragmented and less-politicised use of EU funds for integration in Greece.

Finally, the organisations classified under other migration-related diversity may include a mix of refugees, migrants and others organised together around a specific cause. For example, organisations such as Merhaba in Belgium and Sabaah in Denmark are working to improve the lives of LGBTQI+ persons of migrant and minority backgrounds.

In the Netherlands, the Netwerk van Organisaties van Oudere Migranten (NOOM) [The Network of the Organisations of Elderly Migrants] has been drawing attention to the specific, often-neglected needs of elderly migrants, and runs various projects addressing issues of income, health, the need for culturally sensitive care, and more.

In Luxembourg, the organisations Amitié Plurielle Luxembourg [Plural Friendship Luxembourg] and Association de soutien aux travailleurs immigrés (ASTI) [Association for Support of Migrant Workers], among others, used the momentum created by the Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) report ‘Being black in Europe’ to call in 2020 for the increased human resources and funding for the Centre for Equal Treatment (CET), the national equality body.

On a local level, in the Czech Republic, where municipalities are not obliged to develop their own specific integration strategies, a number of civil society actions, among which Platforma migrant [Migrant platform], helped develop in 2014 the Concept for the Integration of Foreigners for Prague, extended until 2021.

Associations, organisations and membership

On a national level across the EU, out of the 130 structures, 93 are associations, 27 are different types of civil society organisations, and 10 function though some form of a mixed set up which allows them to offer membership that is however not key to their functioning. Similarly, the ratio among these three types of set ups on a local level is, respectively, 18:11:2.

It is important to note that for migrants in Central, Eastern and Baltic states in particular, organisations may be a more viable structure to form.

In Romania, for example, one reason migrants may in general not be able to organise and engage in policy-related work is the aliens act which forbids the association of third-country nationals with the purpose of setting up political parties or other ‘similar organisations or groups’. One notable exception from this region however is Estonia where migrants are more free to form associations – a trends also represented in the dataset.

At the same time, associations are more popular in the traditional migration destination states of Northern and Western countries, as well as in the Southern, although purely migrant-led structures as a whole still appear fewer in Spain, again likely to administrative complications. Over half of the associations that act as umbrellas for other migrant organisations, in addition, are also concentrated in the Northern and Western states.

Individual membership is most common, although traditional destination countries in particular see some larger structures serving as umbrella associations, too. Out of all 130 national-level structures, 67 offer individual membership, but in most cases (40) the actual number of members is not announced. There are at least 13 structures with more than 500 members, and at least nine which count between 100 and 500 members. In addition, 52 structures offer membership to other organisations. Of those larger associations, 35 are in the Northern and Western states. Another 18 offer membership to both individuals and organisations, with half of these again based in the same region.

On a local level, where data is available, 18 offer individual membership, five – membership to other organisations, and three organisations offer both.

Membership in EU or international organisations

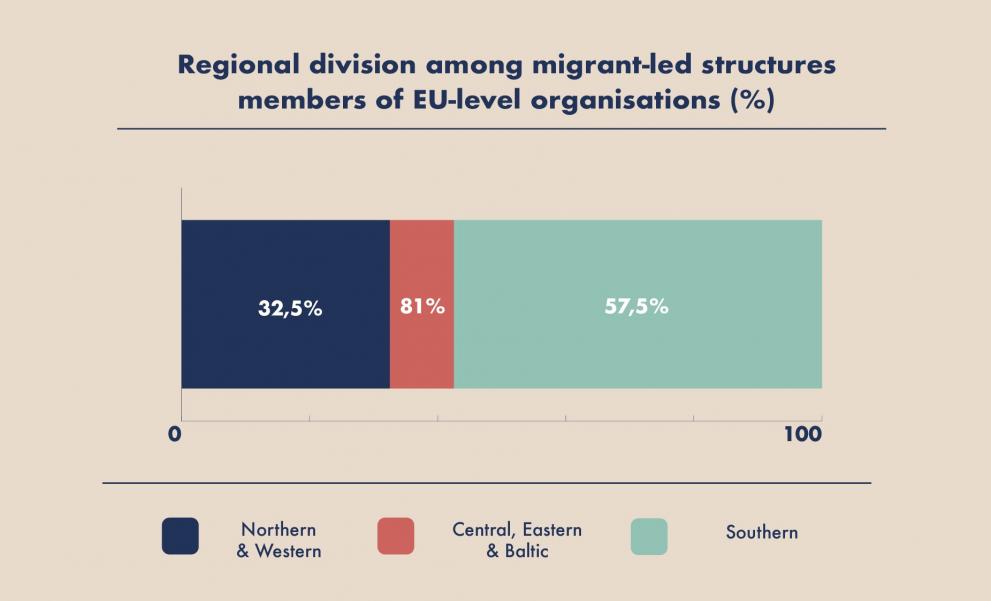

Altogether only 40 – 34 national and 6 local structures – are members of EU or international umbrella organisations. This means that just a quarter (24%) of all the organisations considered are represented in this way.

Over half of these organisations are based in the Southern countries, with the Central, Eastern and Baltic states on the other hand providing the fewest examples.

Most common are memberships in the European Network against Racism (ENAR) with ten organisations, as well as in the European Network of Migrant Women (ENoMW) with seven structures from the set. While there are other important pan-EU or international organisations which address issues often faced by migrants, their members seem to overwhelmingly include national and local organisations which cannot be classified as migrant-led. Check the methodology note to see the umbrella organisations considered, as well as a recent EU-level report on the presence and impact of refugee-led community organisations.

Conclusion

Against the mosaic of bureaucratic realities across the EU countries, migrants still show the determination to self-organise in their own structures. Yet, if migrants’ ability to associate on the ground is still often limited, as also suggested by this earlier study (EPIM 2019), then amplifying migrant voices on a EU level is even more difficult. More attention and support should be paid to the struggles, work and stances of such self-led structures.

To assist in that, EWSI has looked into an initial set of the most active and diverse migrant structures from across the EU, but the current dataset is by no means exhaustive.

Refer to the list of organisations when looking to consult third-country nationals and their descendants in the EU, and help us expand the list by sharing examples of migrant-led organisations and their work – email us at ec-ewsi@ec.europa.eu.

Details

- Publication dates

- Source